How severe mental illness affects physical health management

People with severe mental illness need personalised support to manage long-term physical conditions

Abstract

People with severe mental illness have higher rates of physical illness and a shorter lifespan than the general population. This NIHR Alert discusses a study exploring service users’, carers’ and health professionals’ experiences of severe mental illness co-existing with long-term conditions. It identified that people with severe mental illness need tailored support to self-manage long-term physical conditions.

Citation: Carswell C, Cassidy S (2024) How severe mental illness affects physical health management. Nursing Times [online]; 120: 1.

Authors: Claire Carswell is researcher, University of York; Samantha Cassidy is science writer, NIHR Evidence.

Introduction

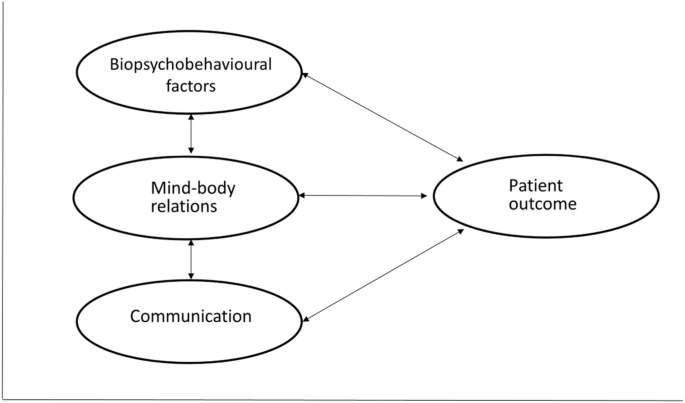

People with severe mental illness (SMI) can struggle to self-manage long-term physical conditions; this article discusses Carswell et al’s (2022) study, in which service users, carers and health professionals described the impact of mental symptoms on physical symptoms and vice versa.

The overwhelming nature of SMI meant service users often prioritised it over physical health. Many were reluctant to engage with services because of previous distressing healthcare experiences, such as being detained involuntarily.

People with SMI live shorter lives than the general population and have higher rates of long-term physical illness, including diabetes and heart disease (Reilly et al, 2015). We found that they, and their carers, need more support than others to self-manage long-term physical conditions.

Our study calls for services that bring together support for physical and mental health conditions. We believe it should inform changes to services to help people with SMI self-manage their physical conditions.

More information about SMI is available on the NHS website at www.nhs.uk/mental-health/conditions

The issue

SMIs are long-term and affect people’s lifestyle, behaviour and family life. Many people with conditions such as schizophrenia have psychosis and lose some contact with reality. They may see or hear things that are not there (hallucinations) and believe things that are not true (delusions).

People with SMI have higher rates of physical illness than those without, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes and heart disease (Reilly et al, 2015). Many have more than one physical health condition. Overall, the life expectancy of people with SMI is 10-25 years shorter than that of the general population (Fiorillo and Sartorius, 2021).

Programmes aimed at helping the general population self-manage physical conditions do not address the difficulties experienced by people with SMI. The barriers to self-management they face include stigma (Clement et al, 2015), discrimination (Shefer et al, 2014) and poverty (Grigoroglou et al, 2020). This could partly explain why previous efforts to help people with SMI make healthy lifestyle changes have had limited success.

Research into self-management programmes tends to exclude people with SMI. In this study, we sought to understand what helps or hinders people with SMIs self-manage their long-term physical conditions. The study was part of a larger project called DIAMONDS, which is investigating tailored solutions to help people with SMI self-manage type 2 diabetes (Siddiqi et al, 2018).

“Service users said they would like to see health professionals who can address both their physical and mental health”

Conducting the study

The study included people who had both an SMI and at least one long-term physical condition. Their carers and health professionals also took part. We conducted 41 interviews and observed people doing an activity of their choice, for example, cooking, food shopping or walking in the park. We also ran five focus groups (two with carers and three with health professionals). Three main themes emerged, which are discussed below.

SMI dominates lives

Service users told us that SMI is unpredictable, inescapable and can be overwhelming. Some carers found their own lives were also restricted by the constant threat of mental health symptoms in the people they care for.

Service users prioritised short-term relief over longer-term health – especially those who struggled with basic self-care, such as showering or exercising:

“I try to do what I can, but some days it’s too hard to do even the basics. I don’t do any cooking for myself or anything like that; that’s all done for me, or I live on things that are straight from the fridge.”

Health professionals added that people smoked and drank alcohol to help them cope with distressing mental health symptoms, despite the fact that this could make their physical health worse.

SMI and physical symptoms interact

Physical symptoms such as pain, fatigue and disability add to the burden of mental illness and can worsen mental health. Medications for mental illness can also have physical side-effects, including weight gain and kidney damage, which can damage physical health over the long term:

“Kidney disease is something that’s ongoing because of my lithium, because I’ve taken lithium for […] 20-odd years. And that causes your […] kidneys to, sort of, not produce.”

Previous distressing healthcare experiences, for example, involuntary detention under the Mental Health Act 1983, made some service users reluctant to engage with healthcare and attend appointments; others were motivated to take medications to avoid another involuntary admission.

People need personalised support

Carers felt that health professionals sometimes think physical symptoms are due to mental illness or do not believe service users have the symptoms they report. This can delay diagnoses. Additionally, carers, family members and friends who help service users attend appointments and interpret information need support to encourage them to self-manage.

Service users said they would like to see health professionals who can address both their physical and mental health. Health professionals believe secondary specialist health clinics need to be reorganised to allow this.

Tailored self-management activities can be developed when service users are asked what matters to them. Service users resisted digital services, often because of concerns that web-based communication might prompt psychotic symptoms, such as paranoia.

One service user said that health professionals for their physical condition could help them to access support for their mental illness:

“I have a community nurse that comes every fortnight who gives me my injection, and she will sit with me for a good half an hour and I can offload to her. And it’s really good that I can have that time and, if anything goes wrong, she can get me an appointment to see my psychiatrist straight away if I need to.”

Why is this important?

People with SMI are at an increased risk of many physical conditions. In addition, they do not have the same experience of healthcare as others and may have been disbelieved or stigmatised in the past. Helping them self-manage their long-term physical conditions might, in turn, improve their mental health.

This study shows that people with SMI, and their carers, need more support to self-manage long-term physical conditions. This could mean home visits from health professionals and increased continuity of care, in which people see the same professional frequently.

Support needs to be tailored. Typically, when people repeatedly miss appointments without giving a reason, they are discharged back to their GP and require a new referral. People with SMI who do not attend appointments need flexible, proactive follow-up and support to help them manage their medication and health. They also need longer appointments, in which both physical and mental health conditions can be discussed, along with enjoyable activities to help them increase their physical activity.

This study did not collect data about people’s characteristics, such as their ethnicity or employment status. Further research could explore whether barriers are the same regardless of these characteristics.

What’s next?

Using our findings, we developed an intervention to help people with both type 2 diabetes and SMI to self-manage their diabetes. This includes an app, as well as a workbook for those who are reluctant to use technology. It is currently being evaluated in a trial across England and Wales (Diamonds, nd).

Key points

- People with severe mental illnesses are more likely to have physical conditions than the general population

- A study investigated how this population self-manages physical conditions

- Service users’ priority is short-term relief from symptoms of mental ill health

- Service users would like to see health professionals who can address both their physical and mental health

- Service users who do not attend appointments need flexible, tailored, proactive follow-up and support

Carswell C et al (2022) The lived experience of severe mental illness and long‑term conditions: a qualitative exploration of service user, carer, and healthcare professional perspectives on self‑managing co‑existing mental and physical conditions. BMC Psychiatry; 22: 479.

Clement S et al (2015) What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking?

A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychological Medicine; 45: 1, 11-27.

Diamonds (nd) Improving diabetes self-management and outcomes for people with severe mental illness. diamondscollaboration.org.uk (accessed 2 October 2023).

Fiorillo A, Sartorius N (2021) Mortality gap and physical comorbidity of people with severe mental disorders: the public health scandal. Annals of General Psychiatry; 20: 52.

Grigoroglou C et al (2020) Prevalence of mental illness in primary care and its association with deprivation and social fragmentation at the small-area level in England. Psychological Medicine; 50: 2, 293-302.

Reilly S et al (2015) Inequalities in physical comorbidity: a longitudinal comparative cohort study of people with severe mental illness in the UK. BMJ Open; 5: 12, e009010.

Shefer G et al (2014) Diagnostic overshadowing and other challenges involved in the diagnostic process of patients with mental illness who present in emergency departments with physical symptoms – a qualitative study. PLoS One; 9: 11, e111682.

Siddiqi N et al (2018) Developing and evaluating a diabetes self-management intervention for people with severe mental illness: the DIAMONDS programme (diabetes and mental illness, improving outcomes and self-management). fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk (accessed 6 December 2023).

link