Exploring the Interconnectedness of Human and Environmental Health: In Conversation with Dr. Arta Yazdanseta

In the evolving landscape of architecture and urban design, bioclimatic and biogenic envelopes present a compelling vision for future cities. Dr. Arta Yazdanseta, a Doctor of Design focused on energy and environments, dives into the intersection of design, building performance, and plant biophysical ecology. With a focus on bioclimatic and biogenic envelopes, Dr. Yazdanseta examines how these typologies can enhance socio-natural systems by leveraging their self-organizing potential. Dr. Yazdanseta’s academic journey includes earning a Doctor of Design and a Master of Design in Energy and Environments from the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Her contributions as a researcher at the Harvard Center for Green Buildings and Cities include developing environmental design strategies and performance analyses for the HouseZero carbon retrofit project. In this interview, Dr. Yazdanseta explores the concept of bioclimatic envelopes and their interaction with passive architectural design principles. With a potential to revolutionize urban environments, the interview reveals insights into her research, the benefits of plant-based materials, and the future of sustainable architecture, emphasizing the critical connection between human and environmental health.

Read on to learn more about bioclimatic envelopes, their benefits, and the future of sustainable architecture.

Related Article

What is Low-Tech Architecture: Comparing Shigeru Ban and Yasmeen Lari’s Approaches

ArchDaily: What is a bioclimatic envelope? How does it integrate with passive architectural design principles?

Dr. Arta Yazdanseta: A bioclimatic envelope uniquely integrates plant-based materials and strategies into wall assemblies, enhancing environmental performance through natural systems. Unlike Passive House design strategies focused on insulation and mechanical systems, this approach uses vegetation like lianas and vines for dynamic insulation, providing shading in hot months and allowing sunlight in colder months. This natural adjustment optimizes indoor climate control and reduces embodied carbon while acting as a carbon sink due to plant photosynthesis. When coupled with the natural ventilation strategy of a building, these vertical porous surfaces can cool the incoming air utilizing canopy transpiration. Additionally, they provide air buffering, reducing infiltration rates and, therefore, buildings’ peak energy use.

At the urban scale, bioclimatic envelopes mitigate the heat island effect, increase biodiversity, manage stormwater, and restore soil health. Moreover, these systems emphasize social justice and equity by improving mental health and accessibility to greenery. Integrating vegetation into buildings provides accessible green spaces, benefiting neighborhoods with limited greenery access, creating healthier urban environments, and addressing multiple community needs cost-effectively.

AD: What initially drew you to focus on bioclimatic and biogenic envelopes? How has this research influenced your general approach to architecture design?

AY: I grew up in Tehran, Iran, in an urban environment with limited access to greenery. Over 25 years ago, when I moved to Brooklyn, New York, I noticed a similar lack of urban vegetation. At that time, urban ecology wasn’t a focal point, and nature was often seen as something outside city limits.

During my graduate studies, my focus shifted from architectural design to building and energy performance. This transition sparked a passion for integrating vegetation into urban settings, driven by my longing for nature in the city. I delved into plant biophysical ecology and incorporated it into building envelope design and energy performance. This journey also unexpectedly led me to engage with material sciences, enriching my approach to sustainable architecture.

A significant realization shaped my research: urban and broader ecological systems are heavily overburdened, and we must promote biodiversity within dense urban areas. This understanding became a cornerstone of my work, driving me to investigate bioclimatic envelopes. These envelopes use plant-based solutions to enhance building performance, improve urban biodiversity, and create healthier, more equitable living spaces.

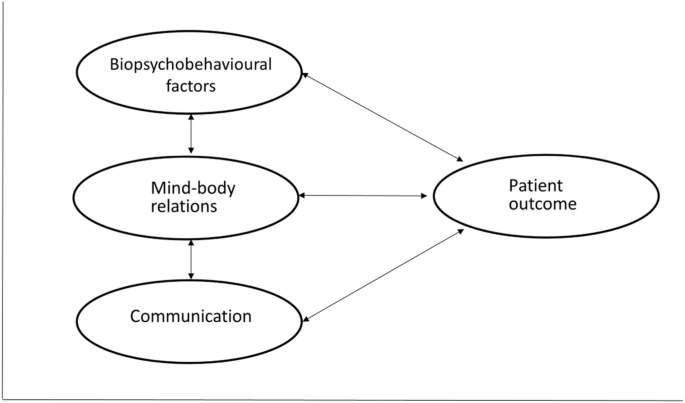

Human and environmental health are deeply interconnected. To support human health, we must support natural systems and ecosystems. Therefore, designs should accommodate both human and non-human needs. This approach ensures architectural designs promote overall well-being and sustainability, highlighting the interconnectedness of human and environmental health.

AD: During your time at the Harvard Center for Green Buildings and Cities, you worked on the Zero Carbon Retrofit project. Can you tell us more about the project? What were the key strategies and design elements that contributed to the success of this venture?

AY: During my time at the Harvard Center for Green Buildings and Cities, I worked on the headquarters’ retrofit project, HouseZero. As one of the first researchers on this project, while pursuing my Doctorate of Design Studies at The Harvard Graduate School of Design under Professors Ali Malkawi and Holly Samuelson, I collaborated with a team of students and experts to develop initial environmental design strategies and performance assessments. The work was then shared with the project’s architect of record, Snøhetta, for refinement and implementation.

HouseZero transforms a 1925 balloon frame construction into a living laboratory for ultra-efficiency and net-zero energy performance, including considerations for embodied carbon. The building operates with 100% natural ventilation, eliminating the need for traditional HVAC systems through a solar vent and operable triple-glazed windows controlled by manual and automated systems. Daylight autonomy is achieved with no electric lighting used during the day, thanks to strategically placed windows and skylights optimizing passive solar practices. Thermal mass and radiant surfaces help regulate temperature, with a geothermal heat pump channeling naturally heated or cooled water through the radiant floors for extreme conditions.

The building has nearly 300 sensors, collecting millions of data points daily to monitor and adjust performance in real-time. These strategies make HouseZero a model of energy efficiency and sustainability, demonstrating the potential for deep retrofitting existing buildings to achieve significant energy and carbon savings.

AD: What are some innovative environmental design strategies that you have personally developed over the years or used in your work?

AY: One of my key innovations is an early design analog tool for evaluating bioclimatic envelopes. This tool assesses the cooling power of solar radiation reduction and transpiration from species like vines. It helps designers determine the viability of bioclimatic envelopes by providing average values for six climate zones.

Additionally, I developed modular support systems using ceramic 3D printing with cost-effective clay bodies for independent vegetative surfaces. Connected to buildings’ gray water, these structures enhance the overall cooling performance of the system by optimizing evaporation. Unlike conventional building systems that separate occupants from the outside, this design strategy promotes a connection to nature by extending the use of natural ventilation. Therefore, the spatial and experiential aspects were integral to the design’s success.

The natural progression of my research led to working with biogenic/ plant-based materials, specifically hemp lime. Hemp lime, made from the woody core of the industrial hemp plant and lime, is an excellent infill for wood frame construction, acting as thermal mass and insulation. Its unique properties allow it to attenuate temperature and control humidity, significantly reducing the operative energy of buildings. Currently, we are investigating different hemp-lime formulations to optimize their thermal and hydrothermal properties for various architectural and environmental design strategies.

AD: In your opinion, what historic or contemporary structure has effectively utilized bioclimatic and biogenic principles?

AY: Three structures stand out, each representing a different point on the development of bioclimatic and biogenic solutions, from historical to futuristic. Historically, the living root bridges of Meghalaya exemplify indigenous knowledge in using plant infrastructure. These bridges, created by guiding the roots of Ficus elastica trees, provide durable, self-strengthening pathways that integrate with the ecosystem, enhancing biodiversity and supporting human and non-human life.

In contemporary times, Nicholas Wiesel’s work with BOXOM demonstrates the practical application of bioclimatic principles through textile farming. This approach uses vertical greenery technologies on urban facades to grow food, provide cooling, and reduce urban heat islands. It introduces an innovative economy by leasing vertical surfaces, integrating environmental benefits at both building and urban scales.

Looking to the future, the Baubotanik projects by Ferdinand Ludwig and Daniel Schönle push the boundaries of biogenic architecture. Using living trees as construction materials, these structures combine botanical growth with technical elements to create dynamic, self-sustaining buildings. This approach marries traditional ecological wisdom with modern technology, aiming to standardize the use of living systems in urban architecture for enhanced sustainability and resilience.

These examples highlight the evolving integration of bioclimatic and biogenic principles, showcasing their diverse benefits from indigenous wisdom to contemporary applications and future innovations.

AD: How do you envision the evolution of passive architecture in the next decade?

AY: The main difference to note here is that passive design is not the same as biogenic or bioclimatic design. Passive architecture traditionally focuses on minimizing energy consumption through design strategies. In contrast, biogenic and bioclimatic design emphasizes integrating plant-based materials for broader environmental benefits, including energy savings.

Local laws, such as NYC’s LL97, are capping operational carbon and will soon address embodied carbon. This shift necessitates using materials that are by-products of other industries. However, there is no universal biomaterial. Architects need to explore the local economy and employ system-level thinking to identify the most suitable plant-based material in their region. Fast-growing materials such as straw, hemp, and bamboo can store carbon in long-life building components. For architects, this means embracing and exploring plant-based materials and identifying local sources to tap into their economic and environmental benefits.

Eventually, buildings will be understood as dynamic entities with local and global environmental benefits. Integrating biogenic materials and innovative designs will address climate change and create sustainable, resilient urban environments. A successful example is the use of hemp-lime in construction, which has shown promise in reducing both operational and embodied carbon. This holistic approach prioritizes both human and ecological health, setting a new standard for future architecture by considering system-level thinking to ensure the health of the environment and humans.

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topics: Passive Architecture. Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and architecture projects. We invite you to learn more about our ArchDaily Topics. And, as always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.

link

![[2025 Physical Health Awareness Survey] Physical Health Self-Assessment and Health Management Efforts [2025 Physical Health Awareness Survey] Physical Health Self-Assessment and Health Management Efforts](https://i0.wp.com/hrcopinion.co.kr/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/iStock-1186136736.jpg?fit=680%2C453&ssl=1)